Sacred cow - the nutritional, environmental and ethical case for better meat

Diana Rodgers, producer and director of the documentary Sacred Cow, wants you to know that eating red meat is good for you and, when raised well, good for the environment.“Cattle have been unfairly scapegoated for our failing health and warming climate,” Rodgers said. “Eliminating livestock from our food system could do more harm than good.”

Rodgers is the producer and director of Sacred Cow, a documentary now streaming on iTunes, Amazon and Vudu that is based on her book by the same name. She is also a registered dietician whose professional opinion is that animal source foods are essential for optimal health, and beef is one of the most nutritious and widely accessible meats available.

“The global dialogue about the future of our food and how to nourish people while being eco-friendly focuses on eating vegan, vegetarian or certainly less meat,” she said. “I challenged that from a nutritional and environmental perspective.”

In the Sacred Cow book, Rodgers and co-author Robb Wolf use scientific data to demonstrate how animal source foods contribute to healthy diets and a healthy planet. The lessons of the book provide the foundation for the film, which covers topics like the rise of industrialized agriculture and processed foods, the food pyramid, and school lunch menus to show how beef has been unfairly stigmatized. Butchers, professors, former vegans and, particularly, farmers take center stage to make a case for raising cattle.

“The film is really [teaching] lessons about regenerative agriculture through producers,” said Rodgers. As explained in the film, regenerative agriculture is “a practice that uses a diverse mix of animals and plants to mimic, rather than dominate, nature” while repairing the soil and increasing productivity on farms around the world.

To illustrate, the film highlights ranchers using such methods to raise cattle that are regenerating more than a million acres of Chihuahuan Desert back into grasslands without using seeds. When cows are frequently moved to graze in a way that mirrors wild herds of ruminants, their manure, saliva, urine and hoof impacts help promote plant regrowth, and overgrazing is prevented.

When properly managed, Rodgers says, cattle help farmland mitigate climate change by storing carbon, which leads to improved water cycles. Of course, the majority of the world’s beef is not produced using regenerative agriculture, and one of the main criticisms of the cattle industry is that it contributes to global warming. While Rodgers acknowledges the problems factory farming presents in terms of animal welfare and poor environmental practices, she says the claim that eating less beef would help slow climate change is overblown.

“We don't have more ruminant animals today in North America than we did in the 1600s before we nearly eliminated the bison,” she said. “They're different ruminants, but we don't have more methane-producing bodies out there.”

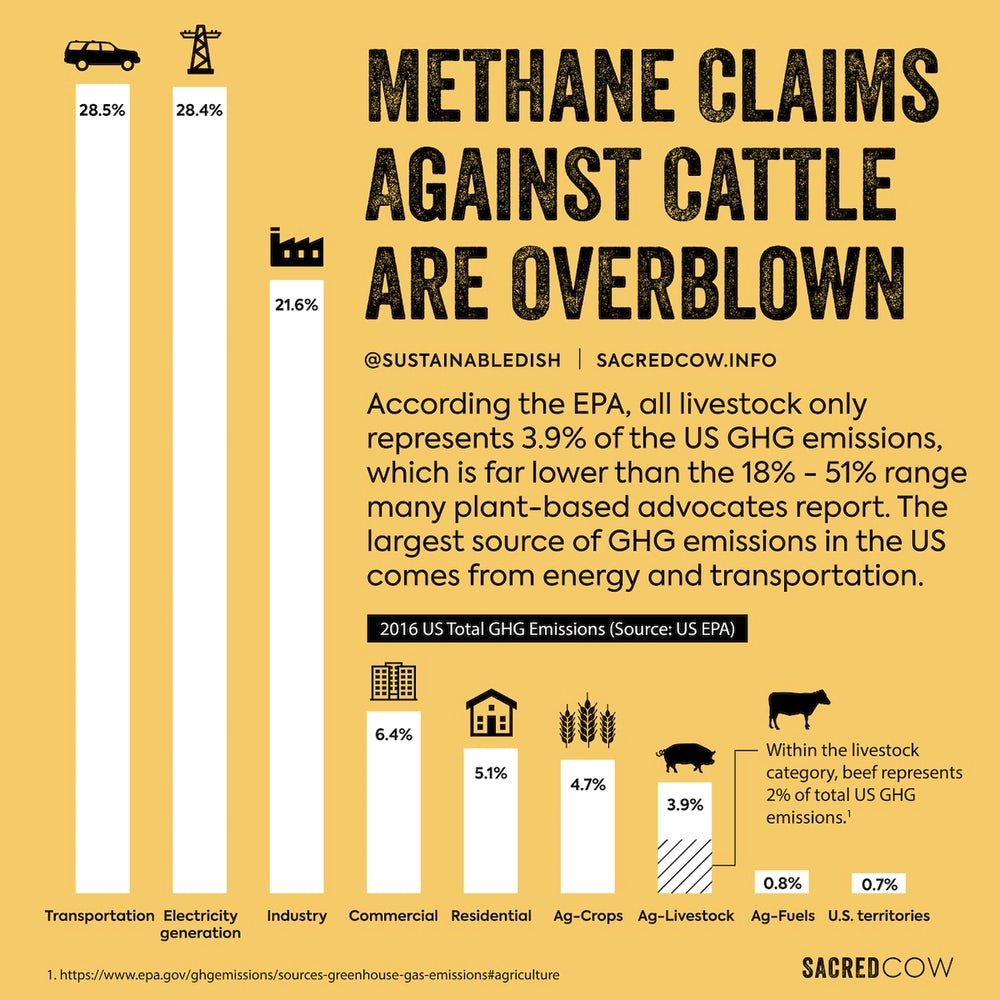

Sacred Cow also contends that the notion of the cattle industry producing more greenhouse gases than the transportation industry is not accurate. Rodgers points to Environmental Protection Agency data, which show that livestock in the US account for 3.9% of methane emissions, with beef responsible for about half that. Transportation and electricity generation combine for almost 57%. Globally, Rodgers says, livestock account for 5% of direct greenhouse gas emissions compared to 14% for the transportation industry.

Additionally, carbon cycles for livestock are different from fossil fuels. “It's part of a natural cycle,” Rodgers said. “After 10 years, methane turns into water and carbon dioxide, which then goes into the water cycle and gets reabsorbed by plants. Some of it can get sequestered in the soil. It’s like a balanced equation.”

From a nutritional standpoint, Rodgers argues that animal-sourced foods are essential because they contain a higher density of nutrients, and humans can better break down and utilize those nutrients when compared to plant-based foods. Some vitamins and minerals — like B12 and iron, which account for two of the largest nutrient deficiencies worldwide — are much easier to get from animals. This is particularly important for growing children and low-income families.

“If we want to feed people who are hungry or undernourished, the most nutrient-dense foods are animal source foods,” Rodgers said. “In developing countries, they can’t just go get their B12 supplement at a CVS Pharmacy, right? Most of the world can’t do that. They require animals for their livelihood and nutrition.”

Sacred Cow also tackles the notion that red meat consumption is the driver of serious health problems in the United States like obesity, diabetes, cancer and heart disease.

“When we look nutritionally at a country where 70% of people are either overweight or obese, our beef intake is actually pretty low,” Rodgers said. “It’s gone down since 1970. The average American only eats about two ounces of beef per person per day.”

With both iterations of Sacred Cow, Rodgers wants to show that meat isn’t the problem and, in fact, is part of the solution. “I’m hoping to effect some policy and make some noise about regenerative agriculture on a bigger scale with the film,” she said. “Now is the perfect time, with COVID,” Rodgers said. “We really see the disruption in industrial meat supply chains and the value people are placing on more regional food systems and better food in general.”

Watch the Sacred Cow Q&A with Diana Rodgers on YouTube.

You can support Heifer International by donating here.