Aussie beef science supports African farmers

Australia's world-leading beef knowledge is being taught to South Africa's smallholder cattle farmers in a project that could deliver rewards on both sides of the Indian Ocean..jpg)

One of the High Value Beef Project's participating farmers with his herd at Mpumalanga.

South Africa’s smallholder farmers, the poorest of the nation’s poor, are being supported by Australian beef industry knowledge in an ambitious plan to put their beef on the plates of the nation’s wealthy consumers.

If some of the world-first strategies for connecting smallholders with premium markets are successful, the concepts may return to Australia to speed up farmer adoption of innovation.

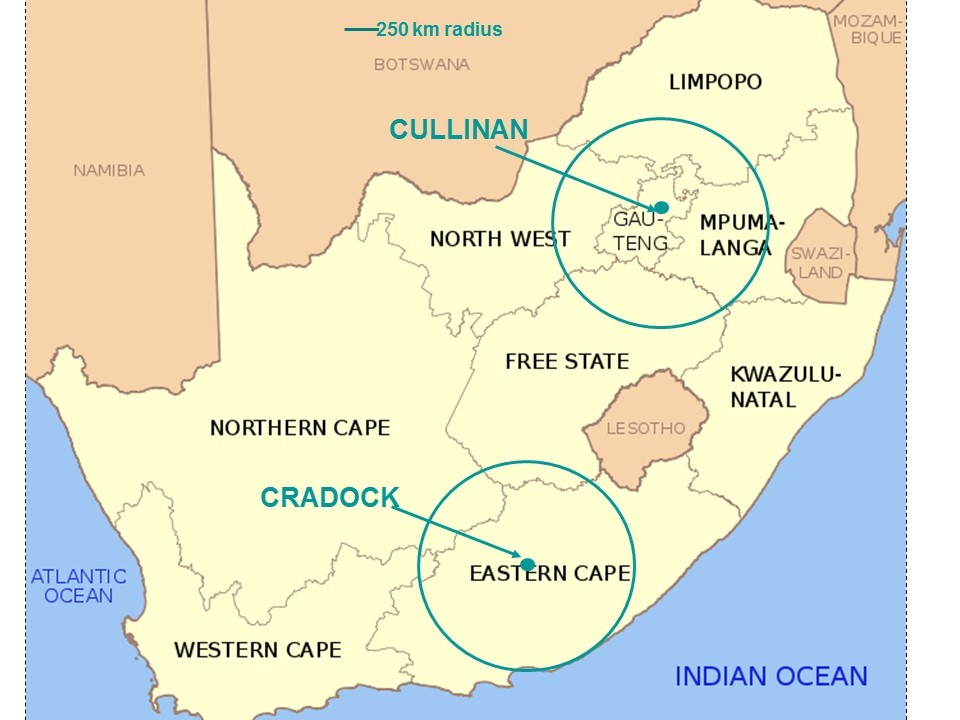

The High Value Beef project is funded by the Australian Centre for International Agricultural Research (ACIAR) and led by former chief executive of the Beef CRC, Professor Heather Burrow, now a University of New England (UNE) Professorial Research Fellow.

One of the Australian beef industry’s most powerful tools, the Meat Standards Australia (MSA) paddock-to-plate grading system, sits at the heart of the African project.

Researchers are using MSA science to help African smallholders meet tight market specifications so that they can sell beef into Woolworths SA’s premium free range beef brand.

Farmers who successfully sell through Woolworths can earn a 15-18 per cent price premium over conventional beef markets.

Prof. Burrow has been working on collaborative projects in South Africa since 1981.

Her current work had its origins in the early 2000s, when the performance of smallholder cattle was compared with cattle from the larger commercial herds.

MSA-guided taste-testing panels (which included imported Australian beef) showed that smallholder cattle could offer the same or better eating traits than feedlotted commercial cattle.

South Africa’s feedlots are heavy users of hormone growth promotants which toughen meat and degrade eating quality.

"Even some nine and ten-year-old bulls from the smallholder herds were comparable to some of the commercial stock," Prof. Burrow said.

In initial tests, smallholder cattle were compliant with Woolworths SA’s free range specifications 65-70% of the time, without interventions to improve cattle management.

However, small farmers culturally prefer to sell older cattle, and don’t have access to good markets, so their animals are sold at a considerable discount to those from commercial herds.

"We tried to find good markets for older cattle, and couldn’t. They are used for weddings and funerals and all the traditional purposes through the informal markets, but they are heavily discounted in the commercial markets."

Enter MSA and its guiding principles (PDF) for producing beef of consistently good eating quality.

To earn the Woolworths premium, beef from smallholder farmers will need to meet the equivalent of MSA eating quality standards, which prescribe the cattle management needed to ensure that beef has the greatest likelihood of meeting important grading criteria.

Some of the changes that African smallholders need to make to target free range market specs include reducing the current stocking rates of their farms and using either planted pastures or supplementary feeds through winter to ensure that sale animals continue growing.

They must also sell off surplus stock, such as cull cows, much sooner than they would traditionally.

"As an instance of the challenges: these cull cows are regarded culturally as ‘grandmothers’. One farmer said to a senior manager that he had to learn to sell his grandmothers."

"Even from a pragmatic business perspective, smallholder farmers normally couldn’t make the required changes, because they would cost too much, but in this case they will be more than compensated by the Woolworths premium."

“But first we have to get enough smallholders prepared to change their management to provide a consistent supply of beef to Woolworths. What seems at first glance to be a business challenge really is a cultural challenge.”

“If we succeed in this, it really could be revolutionary — not just for the smallholder farmers we are working with now, but for smallholders across other provinces, whether they are producing cattle or other commodities.

How an African project may change Aussie farmer extension

An Australian-funded project to give South African smallholder farmers a path out of poverty may deliver an unexpected return to Australian agriculture.

The African business case seems clear cut: if poor smallholder farmers change their management practices so their cattle reliably produce beef to certain quality specifications, South Africa’s Woolworths will pay them a substantial premium to sell their beef as “free range”.

The High Value Beef Project aspires to have about 350 small farmers from each of six provinces involved in the project.

But the cultural obstacles to change are considerable — and not dissimilar to the barriers to adoption of innovation in Australian agriculture.

“To bring these farmers into a specifications-driven production system, we have to design cultural programs that help farmers change their behaviour,” said the South African project’s leader, former Beef CRC chief Professor Heather Burrow.

Psychological profiling of South African smallholder cattle and poultry farmers shows interesting parallels with Australian farmer demographics.

About 15% of African farmers are positive thinkers, representing the innovators and early adopters.

About 15% are defined by negative psychological traits that makes them fearful and resistant to all change, and thus unlikely candidates for the High Value Beef Project.

Prof. Burrow said the remaining 70% might change if there was adequate incentive to do so.

Australian farmers have a very similar industry profile.

Persuading the middle 70% of farmers to adopt new strategies is not merely about making a good business case, Prof. Burrow said. The roots of habit and behaviour go deep.

With that in mind, Prof. Burrow has recruited UNE specialists in psychology, linguistics, and business management to work with African extension officers to create new programs that help farmers overcome personal and cultural resistance to change.

"The interventions we are designing for Africa are world-firsts."

“If we’re successful in Africa, we see potential to bring these interventions into Australian rural research and development extension programs to speed up local adoption of innovation.”