Liver Fluke: The Disease and The Snail

Agricultural consultants are issuing farmers in Western Australia liver fluke advice amid new movement restrictions applying to fluke restricted areas.Outline

Liver fluke, Fasciola hepatica, would be financially devastating to the livestock industries if it became established in Western Australia, as eradication would be almost impossible.

An economic model assessed the likely annual impact of liver fluke on Western Australian agriculture at $8m per year in 2000.

Fascioliasis is a disease caused by liver fluke in the liver and bile ducts of sheep and cattle. However, sheep are more susceptible to the disease than cattle. Horses, deer and goats may also harbour liver fluke and humans too can be infected.

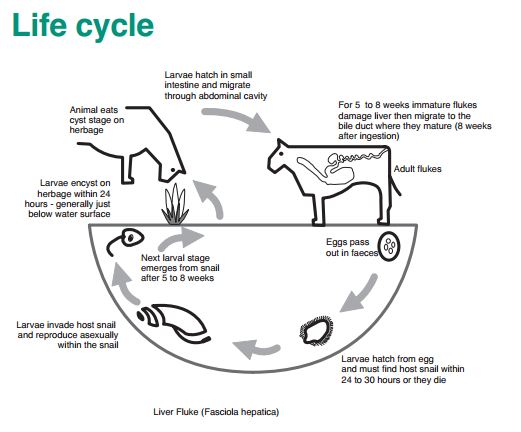

A flat, leaf-like parasite, liver fluke has a complex life cycle. Adult flukes are pale brown or greyish-brown in colour and when mature vary from 15 mm to 40 mm in length and up to 12 mm in width. A liver fluke burden can result in deterioration in wool quality, reduced meat and milk production and ill-thrift in young stock. Stock may die from heavy burdens.

If flukes are detected in livers at the abattoir, the livers are condemned as unsuitable for human consumption.

How is Damage Caused?

After ingestion of infested pasture by a host animal, the young flukes penetrate the animal’s intestinal wall and enter the peritoneal cavity. From there they penetrate the liver where they mature and cause damage as they move around.

The damage done may be so severe as to cause a rupture of the liver capsule and haemorrhage

into the peritoneal cavity, which may result in sudden death. The adult flukes may also cause inflammation to and blockage of the bile ducts leading to jaundice and cirrhosis of the liver.

Liver flukes mature and live in the bile ducts of the host where they lay large numbers of eggs. The eggs are then passed down the bile ducts and enter the intestine to eventually be excreted with

the faeces.

With favourable circumstances—water and moist conditions—the eggs hatch into larvae (miracidia)

which invade the intermediate host, the snail Pseduoduccinea columella. To survive and reach the host snail, which must be within 24 to 30 hours as they have a short life span, the larvae need temperatures above 5°C with the optimum temperature being 15°C to 24°C.

After five to eight weeks and several larval stages later, depending on the temperature, minute tadpole-like larvae emerge from the snail. These larvae form cysts on herbage and are eaten by cattle and sheep. The larvae then migrate to the animal’s liver before entering the bile ducts.

Occasionally a fluke may migrate through other organs or may infect the unborn foetus. The liver is damaged during this migration. This damage alone may kill the animal (usually called acute fascioliasis) or may make it susceptible to black disease, a form of hepatitis.

The Intermediate Host

The snail, Pseduoduccinea columella is one of the several intermediate hosts for the liver fluke and the only one, so far, to be widespread in Western Australia. P. columella has colonised waterways as far south as the Vasse River at Busselton and can be found in most irrigation channels in the south-west which has been designated a ‘restricted area’. This encompasses coastal shires north to Dandaragan,

east to Esperance, and inland to Northam and Manjimup.

Description

An aquatic species, found only in fresh water, it is a native of eastern North America. It competes with established snail species in a variety of environments, and is capable of self-fertilisation. P. columella is a small snail; fully grown it is about 11 mm long with a dark grey body. Its thin, fragile, empty shell is brown and translucent, although some red-brown specimens have been found in areas where a water course is in red soil or clay.

- When viewed from the top, it has a clockwise coil.

- When active, the snail projects through an aperture which is more than half the length of the shell.

- When the snail withdraws, the aperture is plugged with the soft foot; there is no hard operculum. The tentacles on the head are fleshy, flat and triangular-shaped rather than filamentous, as with native aquatic snails.

Habitat

Lakes, ponds, streams, drainage ditches and seepage areas are its home. It prefers sunny, open, shallow pools where there is an abundance of aquatic plant growth and algae on which to feed. On cool, sunny days the snail can be found on the waterline or even a few centimetres out of the water, on the bank. However, it also thrives in deeper waters with grassy edges.