Demand Pull Not Technology Push: Using Drones in Livestock Production

GLOBAL – Applying Unmanned Aerial Vehicles (UAVs) or drones in livestock production has huge potential but producers need tangible cost and profit benefits to embrace them.Inability to demonstrate the effect of remote monitoring of animals on an operation’s bottom line is presently, along with aviation legislation, holding back drones from fully realising potential.

Due to a matrix of factors, livestock producers using UAVs mainly do so for study purposes, rather than the direct functions of crop protection in the arable sector.

Changes are afoot, however, in both UAV capabilities and regulations. US Federal Aviation Authority (FAA) has proposed UAS (Unmanned Aircraft Systems) regulations expected to be ratified in 18 months to two years. Meanwhile, extensive research is ongoing to get the technology to fit the industry.

One such research body is the Commonwealth Scientific and Industrial Research Organisation (CSIRO) in Australia, where Dr Dave Henry is learning about the need of a dollars and cents approach in proving commercial viability of UAVs to farms.

He says that legislation, as well as tight producer margins, are stopping Australian livestock producers from investing.

“It takes a lot of effort to intervene so they have to have a very convincing return on their investment if they are going to do something differently as a result of getting the new information from the drone,” says Dr Henry.

“Compare this with a crop where if a health issue is detected they can readily decide if they go out and spray.”

Key for success, he says, is the combination of timely, accurate information to influence a decision with a level of confidence around the outcome. His answer is “predictive analysis” to inform likely scenarios resulting from interventions.

Is There A Market For Them?

“When it comes to scouting, the last innovation was the work boot,” says Adam Sheller, director at US company, Precision Drone.

He sees a “naked eye picture” as having limited use for a rancher but is enthusiastic about thermal imaging. A hypothesis his organisation is working on is alerting cattlemen to pregnancies via sensing a three to four degree increase in cow temperature.

He says the company covers the US with the most distant order being from Mexico where a drone has been bought to monitor tree health.

*

"When it comes to scouting, the last innovation was the work boot"

“I would say about 20 per cent of the customers that we deal with and talk to are interested in how it can benefit their livestock operation,” says Adam. “We just need something to give them that they see profit in using.”

A UAV can reduce time risk and cost when mustering cattle in the Australian outback and Dr Henry stresses the benefits could be useful for monitoring vegetation and waterways.

Fertiliser and water inputs could be reduced and soil erosion and water run-off minimised, he adds.

Manually checking farm infrastructures would also be reduced by saving on driving time.

Practical Drawbacks

For Penn State University extension agent J.Craig Williams, the benefits of a thermal picture from a UAV are clear. Summing up the current state of play, he says: “I can see my cattle, but right now I need to go to the pasture to see who is in heat.”

However, some say a naked eye view might be enough. Wyoming rancher and Beef Ambassador Rachel Purdy says her family spends many hours driving round their rangelands checking on irrigation and fencing.

“I can definitely see drones being useful on our operation,” she says. “If we could have a drone with a long range, maybe forty miles (approximately 65 km) that would be most useful for us.

“If a drone could go check water tanks and fences, then fly home on its own that would be ideal. At this point in time, this is not possible due to regulations.”

Adam Sheller says: “40 miles might be useful in Wyoming, but I feel that something like that would be very irresponsible to put into the air.

“Currently this is possible through stronger signals than are allowed in the civilian range. I don’t think we’ll be at that point for a while.”

Another setback is battery life when covering large distances. A practical way round this could be to run several platforms, relaying information between each other.

This is according to Lia Reich, communications director at Precision Hawk, who adds: “Battery life is an issue and generally our batteries are good for around one hour at a time.”

She is also of the opinion that data is key to progress and analytics packages can maximise value for what are expensive and sophisticated machines.

“We’ve seen a lot farming families invest in drones but there is a wealth of data that they have no idea what to do with,” says Lia. “One of our focuses is data analysis – we like to produce an actionable result and bring benefits.”

Wind is a further factor to consider. Geography and seasonality dictate what wind speed tolerance is practical but generally 25 mile per hour is the cut-off point.

“Wind is a big deal,” admits Adam Sheller. “Quadcopters can handle about 15 mph wind at max and our hexicopter can handle up to 30 mph. That is in our mind enough because any more than that can be storm weather activity anyway.”

It is a trade-off between getting data at all and getting good data. Similarly, speed of travel is a factor with good quality data being captured at around 25 miles per hour and quality dropping much above this.

Evolving Regulations

Varying levels of restrictions are in place on UAVs. Countries like the US, UK and Australia have strict laws on where they can be flown and for what purpose.

For now, the UK’s airspace has little space for drones, according to Professor Toby Mottram, Royal Agricultural University.

He sees legislation and technology as potential answers to this fundamental issue.

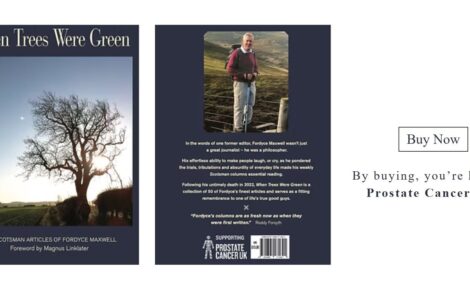

A UAV at a testing facility. Photo courtesy of OSU

“These devices are covered by Civil Aviation Authority regulation and 90 per cent of the UK is controlled airspace,” says Professor Mottram. “So, in commercial applications there must always be a pilot, if only to shut the system down when an emergency flight needs the airspace.

“Much of the regulation is being rewritten and software could solve many of the problems such as limiting where and how high the devices could fly.”

He adds: "I think the enthusiasm for drone technology more correctly known as RPAS - Remotely Piloted Aviation Systems - tends to outrun the commercial applications."

Meanwhile, farmers in the US and Australia have a 400 feet maximum height rule and laws about keeping the UAV in sight; observing strict trespassing laws and staying clear of other flight paths.

Pending FAA guidelines will mean unmanned aircraft are not operated:

- More than 500 feet above ground level

- More than 100 mph.

- After daylight, which is the time between official sunrise and sunset.

- When there is not minimum weather visibility of 3 miles from the aircraft’s control station.

- No closer than 500 feet below and 2,000 feet horizontally away from any clouds.

- Over any persons not directly involved in the operation and not under a covered structure that would protect them from a falling UAS.

- From a moving aircraft or vehicle, unless the moving vehicle is on water.

- Within Class A airspace; or within Class B, C, or D airspace or certain Class E airspace designated for an airport, without prior authorization from the appropriate Air Traffic Control facility.

- Carelessly or recklessly, including by allowing an object to be dropped from the aircraft in a way that would endanger life or property.

This is according to agricultural law expert Professor Peggy Kirk Hall, Oklahoma State University (OSU), who states that the rules fail to address issues of privacy and surveillance of neighbour’s property.

“Many in the agricultural community worry about the potential use of drones for surveillance activities that violate a property owner’s privacy,” writes Professor Hall in a recent article. “The FAA states that privacy concerns about unmanned aircraft operations are beyond the scope of this rulemaking.”

Concerns may also surround the “visual line-of-sight” rule, meaning farmer eye contact is kept on the UAV, she adds.

And while rules may appear onerous, most in the industry understand that they are responsible.

“The FAA has a lot of things to consider,” says Lia Reich, who sees it as a balance between safety, practicalities and privacy.

“People need to feel comfortable about this technology, this means talking to the media and educating the public. We get bombarded with stories about “mystery drones” but people are not seeing the great things from drones that we see in the industry every day.”

She adds, however, that much more relaxed regulations exist in South America, where large scale trials can be done assessing the capabilities of UAVs on extensive livestock operations.

“This is one of the perks of working with big multinational companies,” says Lia Reich. “This is why its important to have a global presence – studies can be carried out in Argentina and Brazil.”

Problems can be ironed out and US farmers can then get to work with the UAVs right away, she explains.

Drones in the Future

Also at OSU, studies are looking at the use of UAVs in agriculture, where Dr Jamey Jacobs sees agricultural implementation as more relevant for cropland than cattle.

“A drone’s primary capability here is using visible and infrared imaging – there’s a lot more utility for cropland,” says Dr Jacobs.

He says locating cattle can be possible with infrared when under trees and, legislation depending, at night time.

“Current use is mostly based around checking conditions and cows,” he explains. “This is useful if you have a pregnant cow some distance away, it wanders off and you don’t know about it.”

And he says it will be a while before you simply press a “green button” for autonomous operation.

“There is some good technology out there right now but there is a steep hill to climb in operating these things. There’s still training that pilots and farmers have to do.”

Looking at the next generation of farmers, Dr Jacobs says that people are keen to take technology back home after coming to University. He has seen a resurgence of ideas that have been a “boost to the sector.”

For some, the future is about developing the technology to heighten the level of data capture and analysis to provide more insight for the farm.

“Why buy a $20k UAV when you can get one for $500?” asks Lia Reich. “It’s all about the level of intelligence built into the platform.”

“Next thing we could see happening is the drones themselves getting smarter. Lots of Artificial Intelligence will be packed onto each platform.”

In terms of the slower rate of adoption, it’s not that crop producers are more progressive, it’s a case of the livestock sector being more constrained, according to Dr Henry.

“Dealing with individual animals moving across large distances and making individual choices about the vegetation they consume are the constraints,” he explains.

He adds that key decisions on the productive life of animals need optimising in terms of impacting the final product.

Michael Priestley

News Team - Editor

Mainly production and market stories on ruminants sector. Works closely with sustainability consultants at FAI Farms